A day in no-man’s land ©2004

NOTHING but dusty potholes and loose gravel roads lay between Marawi City and the town that lies 32 kilometers further south of the city outskirts. It was once called the no-man’s land of Lanao del Sur which is on the island of strife-torn Mindanao.

In a 2000 census, the town of Maguing listed 18,095 residents and all of them are Muslims. Not a tincture of Christian blood could be found in this town that even Muslims from Marawi City are sometimes reluctant to go to.

NOTHING but dusty potholes and loose gravel roads lay between Marawi City and the town that lies 32 kilometers further south of the city outskirts. It was once called the no-man’s land of Lanao del Sur which is on the island of strife-torn Mindanao.

In a 2000 census, the town of Maguing listed 18,095 residents and all of them are Muslims. Not a tincture of Christian blood could be found in this town that even Muslims from Marawi City are sometimes reluctant to go to.

When the group I was with visited Maguing in September 22, 2004, it was the first day of Ramadan. Almost every Muslim we met was in a state of piety that day. For more than a billion Muslims worldwide, Ramadan is a time of prayer, fasting, and charity.

Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar. Islam uses a lunar calendar where each month begins with the sighting of a new moon. The lunar calendar is about 11 days shorter than the solar calendar which is used elsewhere.

A young Muslim teacher told me that Islamic holidays ‘move’ each year. This year, however, Ramadan began on September 24. Ramadan also precedes Christmas and Hanukkah. In many places, the two Christian and Jewish holidays has become widely commercialized. Ramadan, on the other hand, retains its focus on self-sacrifice and devotion to Allah (God).

I asked myself why Muslims observe Ramadan on September. I found out that Muslims believe that Allah revealed the first verses of the Qur'an, the holy book of Islam, on a September. Around 610 A.D., a caravan trader named Muhammad wandered on the desert near Mecca (in today's Saudi Arabia) while thinking about his faith. One night a voice called on him from the night sky. It was the angel Gabriel who told Muhammad he had been chosen to receive the word of Allah. In the days that followed, Muhammad found himself speaking the verses that would be transcribed as the Qur'an.

During Ramadan, about one thirtieth of the Qur'an is recited in mosques each night in prayers known as tarawih. Through this process, the complete scripture will have been recited in the whole month of September.

During Ramadan, Muslims practice sawm, or fasting, for the entire month. This means that they may eat or drink nothing, including water, while the sun shines. Fasting is one of the Five Pillars (duties) of Islam. As with other Islamic duties, all able Muslims take part in sawm starting from age twelve.

During Ramadan, Muslims close their restaurants during the daylight hours. Families get up early for suhoor, a meal eaten before the sun rises. After the sun sets, the fast is broken with a meal known as iftar. Iftar usually begins with dates and sweet drinks that provide a quick energy boost. In Maguing, only the small stores remain open.

For the Muslims of Lanao del Sur and in other parts of the world, I was told that fasting serves many purposes. While experiencing hunger and thirst, Muslims are reminded of the suffering of the poor. Fasting is also an opportunity to practice self-control and to cleanse the body and mind. And in this most sacred month, fasting helps Muslims feel the peace that comes from spiritual devotion as well as kinship with fellow believers.

In Lanao del Sur, Maranao is the most commonly spoken language. Also spoken by the people are Tagalog and Cebuano, as well as English and Arabic.

The native Maranao of Lanao del Sur have a fascinating culture that revolves around kulintang music, a specific type of gong music, found among Muslim and non-Muslim groups of the Southern Philippines.

Lanao del Sur forms the western portion of Northern Mindanao. It is bounded on the north by Lanao del Norte, on the east by Bukidnon, on the west by Illana Bay, and on the south by Maguindanao and Cotabato. The landscape is dominated by rolling hills and valleys, placid lakes and rivers.

Imams or Muslim holy men are regarded as caretakers and keepers of mosques. These savants are considered the elder wise men of Islam and are accorded respect.

The climate in the province is characterized by even distribution of rainfall throughout the year, without a distinct summer season. The province is located outside the typhoon belt.

When my group arrived in Maguing in the middle of the night, it was freezing cold. I wondered why we had to travel at night on this seemingly dangerous area. Our good host was a relative of the mayor and is regarded to be one of the most influential people in the province.

This is not the first time I traveled outside Marawi City. I have been to other Lanao municipalities but traveling in this remote area at night really gave me the goose.

Marawi City is the capital of Lanao del Sur, a principality that lies on the northern part of Mindanao. It is a rugged territory overlooking picturesque Lake Lanao. The province belongs to the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) where an election for a new governor recently took place. The election results were marred by complaints of frauds filed by candidates who lost.

Lanao comes from the word ranao, meaning "lake." Lanao centers on the basin of Lake Lanao; thus, it is the land of the Maranaos, the "people of the lake."

When the Spaniards first explored Lanao in 1689, they found a well-settled community called Dansalan which was located at the lake's northern end. Dansalan became a municipality in 1907 and a city in 1940, although it was inaugurated as such only in 1950. In 1956, Republic Act No. 1352 changed the name Dansalan to Marawi, from the word rawi, referring to the reclining lilies in the Agus River.

When Lanao was divided into two provinces under Republic Act No. 2228 in 1959, Marawi was made the capital of Lanao del Sur. In 1980, the city was renamed the Islamic City of Marawi. It is now the only chartered city in the country with a predominantly Muslim population. In a 1989 plebiscite, Lanao del Sur voted to join the ARMM, but Marawi City elected to remain outside ARMM.

The long bumpy ride from Marawi City to Maguing eventually brought us to a wooden bridge built over the Potian River, a tributary that connects to Lake Lanao. The river is the source of life for the residents of this town. It provides the water needed to wash their clothes and irrigate their farmlands. It is also the source of deep wells that provide the drinking waters they need for daily nourishment.

Our guide and host, Abdulrashid Ding Ladayo, a resident Muslim and a former Manila Times correspondent, told me that my group of five are the first non-Muslims to be accorded entry into their town for a very long time.

“The people of Maguing are very friendly but they are also very suspicious of unfamiliar faces,” Ladayo said. “That is probably the reason why Christians are hesitant to come here.”

The 6th class town of Maguing is as rustic as ever. Except for a few material objects like color televisions, DVD players and mini-components, no other un-Islamic influence can be found here – albeit for the more obvious shampoo and election posters stapled or plastered on walls of sari-sari stores and electric posts.

A few roads leading to the municipal building are paved but the rest that led to the town’s 36 barangays are indications that government has long forgotten this enclave.

A golden mosque in Barangay Pagalongan stands still as a symbol of the Islamic faith. In the morning, a call for prayers echo from the minaret as the imam recites verses from the Qur'an - calling the faithful to worship Allah.

Since it was Ramadan, the residents of Maguing were more attentive to their religiosity rather than to pry on us.

Once a hotbed of the secessionist war, the mountainous terrain that surrounded the town still cast a shadow of death and destruction.During the onslaught of the Moro rebellion against the Marcos government in 1972, fierce battles between the Philippine Army 6th IB Tabak Division and 5,000 Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) fighters and a special guerilla unit under the command of Commander Narra raged in the thick jungles of Karandangan Kalasan, for 76 days and nights.During the battles and skirmishes, hundreds of government troops were reported killed in this unfamiliar terrain while a lesser number was suffered by the rebels.

Today, after three decades of conflict, an uncertain peace has finally nestled on the fertile grounds of Lanao del Sur, or at least in this municipality, where the legendary Sultan Mangoda Hadji Salam, also known as Commander Tiger of the MNLF Central Ranao Revolutionary State, now finds solace. Salam is now a farmer and the president of the Parents-Teachers Association (PTA) of the Benito Memorial High School in Barangay Pagalongan.

“I prefer to farm now than fire my rifle,” Salam said. “War is terrible. The faces of death are simply unforgettable.”

According to a published report by the Livelihood Enhancement and Peace (LEAP) Program, a macro-economic project partly sponsored by the US and Philippine governments, Commander Tiger’s name was synonymous to notoriety especially to people he once regarded as enemies. But in 1996, this reputation was put to a test after the Philippine government and the MNLF signed a peace accord ending more than 20 years of armed conflict.

“It was not an easy task, Commander Tiger said. “When I returned, the place was almost deserted. It had become a vast wasteland with tall grasses reaching as high as three meters,” he recalls. “Most of the residents have relocated to Marawi City.”

The once fearless leader have turned to farming ever since the LEAP Program provided him, and 74 other former MNLF combatants in the area, with production inputs and technical means for agricultural production.

“I was away from my wife and seven children for a long time. I did not even see my children grow up,” he said.

Commander Tiger’s leadership skills, honed in the guerilla movement, were put to good use when LEAP was introduced to his hometown in 1997.

“Most members were skeptical about the project,” he recounts. “I had to show them that we could do it.”

He braved the heat of the sun and planted corn himself. Today, aside from being an entrepreneurial farmer, Commander Tiger also spends time to look into the affairs of the Benito Memorial High School, where he is the current PTA president.

“I was away from my wife and seven children for a long time. I did not even see my children grow up,” he said.

Commander Tiger’s leadership skills, honed in the guerilla movement, were put to good use when LEAP was introduced to his hometown in 1997.

“Most members were skeptical about the project,” he recounts. “I had to show them that we could do it.”

He braved the heat of the sun and planted corn himself. Today, aside from being an entrepreneurial farmer, Commander Tiger also spends time to look into the affairs of the Benito Memorial High School, where he is the current PTA president.

The school was built in 1998 on a lot donated by Sultan Tingagen Macaaqir. When I was there, the teachers here lamented to me that the government has not paid them their back wages for six months.

When the group I was traveling with, arrived to donate DepEd-approved textbooks purchased through an NGO-LGU partnership program, the school suddenly burst with activity.

“The government does not provide us with books that will help educate the children of Maguing,” said Tapnai Molok, OIC principal of the Benito Memorial High School. “If not for your books, then we will practically have nothing to read.”

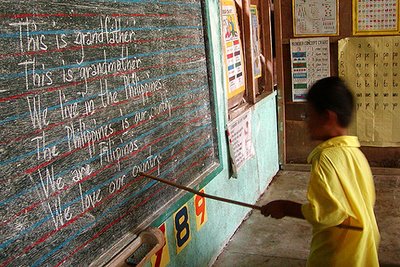

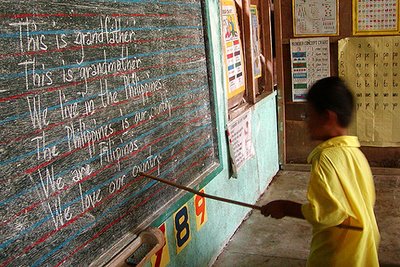

Perennial problems mentioned by Molok is a redundant cry bewailed by teachers in almost all public schools in Mindanao. A few blocks from the Benito Memorial High School is the partially-dilapidated Malungun Elementary School. I was surprised to see a grade three pupil struggling - with twisted tongue - to recite in broken English, a Philippine patriotic poem scribbled on the blackboard by his teacher.

The classroom was unlit except for the morning sunlight that made its way through the embroidered drapes. The Muslim teacher said they had to make do with available sunlight to illuminate the room, and normally, classes are dismissed before lunch.

But despite the primordial needs of the schools here, the town of Maguing seems to be thriving to move onward from its arrested development. New roads, bridges and other infrastructures are still awaiting construction by the administration of Mayor Hakim Abinal.

Despite the optimistic vision of transforming the town into a more social-friendly habitat, contrasting sights seemed quite noticeable. In a semi built-up area, Dream cable satellite discs mounted on rooftops of several residential houses reflect the status of the dwellers – it is also an indication that the well-off residents of Maguing are hungry for news from the outside world.

It seems rather odd, however, that parents who earn a living from whatever means could afford to spend money to buy televisions and DVD players, yet could not provide the needed books for their children. Searching for logical answers, I began to wonder: “Where do the people of Maguing get their livelihood, aside from planting rice and corn?” I expected an answer from my host but he simply shrugged off the question with a smile.

On the road again, and on our way back to Marawi City after spending a freezing evening in one of the more comfortable modern houses found in no-man’s land, Mitsubishi Pajeros and colorful jeepneys would again zoom past us – all heading to the direction of Maguing and vice-versa.

Despite the bad roads, old dilapidated houses, and a few stylish concrete houses, and whether or not it is a sign of suspended progress and prosperity, this old town branded with infamy during the war years seemed to be willing to catch up with the rest of its neighbors.

After my visit to the place, my Muslim friends from the academe who are based in Marawi City asked me with great amazement, why, of all places in Mindanao, did I go to Maguing? Rumor goes that a lot of illegal activities happen in this remote town. However, nothing of that sort came to my attention. All I saw were several late model Pajeros with unsuspecting drivers and passengers passing by the gravel road. Then I wondered how much a Pajero costs.