Endless nirvana in Montemar ©2006

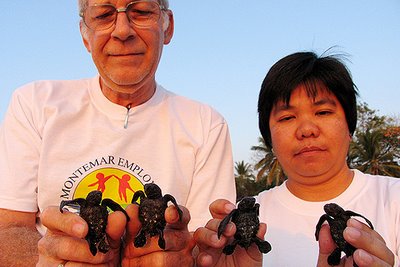

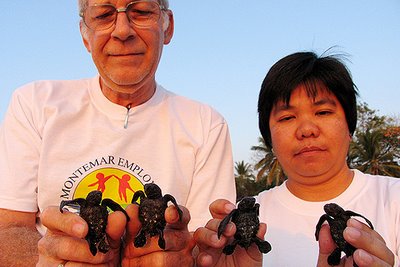

NOVEMBER is pawikan month in Bagac, Bataan. In Filipino parlance, a turtle is called a pawikan. The pawikan in Bagac Bay like to lay their eggs at Montemar beach because in a sense, they feel safe and assured that their hatchlings will find their way to the sea where they truly belong.

Unlike in other coastal municipalities in the Philippines, pawikan are mercilessly slaughtered for their meat and shells. Their eggs are being sold to aphrodisiac freaks for a meager sum of ten pesos (.20 US cents) each. I have heard of tales from fishermen that a pawikan sheds tears when about to be butchered.

NOVEMBER is pawikan month in Bagac, Bataan. In Filipino parlance, a turtle is called a pawikan. The pawikan in Bagac Bay like to lay their eggs at Montemar beach because in a sense, they feel safe and assured that their hatchlings will find their way to the sea where they truly belong.

Unlike in other coastal municipalities in the Philippines, pawikan are mercilessly slaughtered for their meat and shells. Their eggs are being sold to aphrodisiac freaks for a meager sum of ten pesos (.20 US cents) each. I have heard of tales from fishermen that a pawikan sheds tears when about to be butchered.

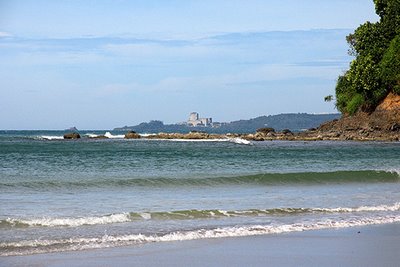

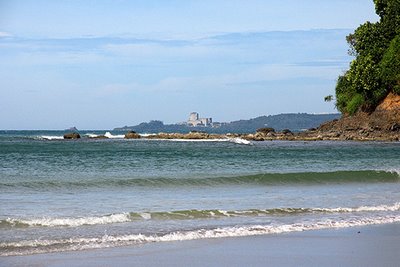

Montemar beach is a beautiful place to unwind. I have been going back and forth to the place since I first arrived in Bataan in 1980, to work in the documentation of the construction of the Philippine nuclear power plant. Unfortunately, the plant was mothballed in 1985 due to political pressures from anti-Marcos groups.

Bataan is a peninsula located in Central Luzon. It has several picturesque mountain ranges where Communist rebels once roamed. Although the big trees in the mountains and forests of Bataan are rapidly being felled by unscrupulous loggers with their chainsaws, the terrain still looks virginal. Today, only a handful, hardcore rebels still make Bataan their enclave. No more ratatat in Bataan.

Montemar beach is on the western side of the Bataan peninsula. It is facing the blue South China Sea. Today, the place is known as an exclusive resort where Manila’s affluent come to escape the hustle and bustle of the metropolis.

Montemar beach is about two kilometers from my house in Bagac and for 27 years served as my place of retreat. Whenever I wanted peace of mind I go to this place. Whenever I need to meditate I go to this place. Whenever I need to drink ice-cold San Miguel I go to this place. The Montemar pool is also a nice place to jump into on a hot sunny day. Yes … never was there a dull moment I could think of every time I talk about this beautiful place.

The town of Bagac is exactly 151 kms. from Manila by car - about two hours drive on a normal day. Driving at night would be much quicker. It can also be reached by overloaded motorized banca (outrigger) from Morong and Mariveles.

In Montemar, Pawikan Day is celebrated on the fourth day of November. And on the 25th of the same month, the residents of Bagac celebrate the birthday of their patron Saint Catherine de Alexandria. Bagac is a predominantly Roman Catholic town. Just like in any municipality in the Philippines, the people of Bagac religiously go to church every Sunday to hear mass. The followers of el Shaddai congregate at the town plaza once a week to sing their songs of joy and miracles. And much of every weekend, visitors and tourists also flock to this town. Yet the town remains sleepy.

In the last three years, the management of Montemar Beach Club has entered into a joint agreement with the Community and Environment and Natural Resources Office and the local government unit to protect the pawikan found in Bagac Bay.

Since then, hundreds of pawikan – Olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) turtles in particular - had been saved. Thousands of hatchlings had been released to the sea. The management of Montemar Beach Club has constructed a recovery and rehabilitation pond just near the water, were wounded and exhausted pawikan can be treated and released back to the seas.

I heard that the Olive ridley turtles are now endangered in Mexico and threatened elsewhere. The turtle was named after H.N Ridley FRS, who was on the island of Fernando de Noronha, and in Brazil in 1887. As both its common and species names imply, the overall color of this turtle is olive green.

I was also told that the Olive has a sister specie which is called the Kemp's ridley. It is a small sea turtle, usually less than 100 pounds (45 kilograms). The most obvious difference between the Olive ridley and the Kemp's ridley is the number of costal scutes of the upper shell. The olive ridley has from 5 to 9 costals and 7 vertebral scutes. Kemp's ridley has 5 costals, and 5 vertebrals.

Not so long ago, these turtles were called the Pacific and Atlantic ridley respectively, but the discovery of Lepidochelys olivacea off the Atlantic coast of South America necessitated a name change. This is an omnivorous turtle which feeds on crustaceans, mollusks and tunicates. An average clutch size is over 110 eggs which require a 52 to 58 day incubation period.

The Olive ridley inhabits tropical and subtropical coastal bays and estuaries. It is very oceanic in the Eastern Pacific and probably elsewhere too. These animals are found in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and along the Atlantic coast of West Africa and the Atlantic coast of South America. How they found their way to Montemar, only God knows.

In the Eastern Pacific it occurs from Southern California to Northern Chile. Large nesting aggregations called "arribadas" still occur in Pacific Costa Rica, primarily at Nancite and Ostionales and Pacific Mexico at La Escobilla, Oaxaca. According to the Marine Turtle Newsletter (October 1993), an estimated 500,000 nesting females came ashore during a single week in March, 1991 at Gahirmatha Orissa, India.

According to a current threats and historic reasons for decline in the number of global Olive ridley turtles, the last large arribada beach in India is threatened with disaster by the development of a major fishing port and a prawn culture facility. In fact, it threatens the entire Bhitarkanika Sanctuary in which the beach is located.

On the Mexican Pacific Coast of the states of Jalisco, Michoacan, Guerrero and Oaxaca, past large scale exploitation for meat, eggs and leather reduced the once large arriabas to dangerously low levels. In June of 1990, Mexico declared total protection for this species as well as the other species of sea turtles inhabiting Mexican waters, but there is still a trade on the black market.

In 1993, 350,000 nests were recorded in Escobilla, Oaxaca (Marquez, 1994, pers. comm.). Mexico has recently opened the Mexican Turtle Center at Mazunte, Oaxaca, near the site of a former turtle slaughter house. Hopefully, some of the same individuals who formerly killed turtles will be able to earn a living by protecting them and educating visitors about them. Despite Mexican initiatives to protect the Olive ridley, this same population is still exploited in the black market in Mexico and harvested as it feeds along the Pacific coasts of Nicaragua and Ecuador. In Bagac, Bataan, a group of marginal fishermen banded together to protect and preserve the Olive ridley that arribada in the coastal areas of the municipality.

A closer look at the pawikan, one will notice that the head of an Olive ridley is quite small. Carapace is bony without ridges and has large scutes (scales) present. Carapace has 6 or more lateral scutes and is nearly circular and smooth. Its body is deeper than the very similar Kemp's ridley sea turtle. Both the front and rear flippers have 1 or 2 visible claws. There is sometimes an extra claw on the front flippers. Juveniles are charcoal grey in color, while adults are a dark grey green. Hatchlings are black when wet with greenish sides.

An adult Olive ridley measures 2 to 2.5 feet (62-70 cm) in carapace length and weights between 77 and 100 pounds (35-45 kg).

They can be found in coastal bays and estuaries, but can be very oceanic over some parts of its range. They typically forage off shore in surface waters or dive to depths of 500 feet (150 m) to feed on bottom dwelling crustaceans.

They nest twice every year and lay an average of over 105 eggs in each nest. Eggs incubate for about 55 days. An average clutch size is over 110 eggs which require a 52 to 58 day incubation period.

Under the U.S. Federal Endangered Species Act, the Olive ridley is listed as ‘Threatened (likely to become endangered, in danger of extinction, within the foreseeable future).’ It is also listed as ‘Endangered (facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild in the near future)’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

Threats to survival of these turtles are the direct harvest of adults and eggs, incidental capture in commercial fisheries and loss of nesting habitat are the main threats to this species. The Olive ridley has a global population estimate of 800,000 nesting females. The Olive ridley's life span is believed to be between 50 and 60 years. They reach reproductive maturity at 10 to 15 years of age, and are reproductively active for nearly 21 years.

Olive ridley nest (lay their eggs) in large groups of females called arribadas or arribazones (a derivation of the Spanish word for "arrival"). In preparation for the arribada, females gather off the coast, and then emerge to nest together ashore. In the past, as many as one million nesting females have been seen during an arribada that spanned several days on the same beach. Today, Olive ridley arribadas consist of, at most, a few thousand nesting females.

The main nesting grounds are on the shores of the Pacific Ocean around Costa Rica, Mexico, Nicaragua, and the Northern Indian Ocean, where the turtle nests abundantly in eastern India and Sri Lanka. Olive ridleys nest two to three times per nesting season, which occurs every one to two years. Nesting, which always occurs at night, takes between 45 minutes to an hour, after which time the female ridleys return to the ocean and disperse in many different directions. Depending on geographic location, nesting occurs from June to December, peaking in September and October. After a 55-day incubation, hatchlings emerge from the nests small—about 1.5" long and weighing less than an ounce—and are black with greenish sides

Of all the sea turtles, Olive ridley populations are relatively healthy. Still, there are so few left that in 1978, the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) listed the Mexican nesting populations of Olive ridleys as endangered—and all others throughout the world as threatened. Despite this action, Olive ridley populations have actually shown a decline in abundance since their ESA listing as threatened, and at this time, the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) lists all populations of olive ridleys as endangered. Olive ridleys are also listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora (CITES), which means that trade in Olive ridleys, their eggs or any part or product derived from the turtle is forbidden.

Olive ridleys suffer high mortality rates from gill nets and trawl fisheries. They also fall victim to water pollution. Adding to these environmental hazards, the Olive ridley is jeopardized by trade, too: highly prized in Japan for its meat and eggs, the turtle is illegally hunted to supply this trade. Finally, occasionally on beaches where arribadas occur, there is a natural breakdown of nest contents, which creates fungus and bacteria that destroys the buried sea turtle eggs. This natural occurrence contributes to large discrepancies in Olive ridley populations from year to year.

Olive ridleys suffer high mortality rates from gill nets and trawl fisheries. They also fall victim to water pollution. Adding to these environmental hazards, the Olive ridley is jeopardized by trade, too: highly prized in Japan for its meat and eggs, the turtle is illegally hunted to supply this trade. Finally, occasionally on beaches where arribadas occur, there is a natural breakdown of nest contents, which creates fungus and bacteria that destroys the buried sea turtle eggs. This natural occurrence contributes to large discrepancies in Olive ridley populations from year to year.

In Montemar, the Olive ridley turtles have attracted more visitors to the resort. Children are the number one fans of the pawikan. The children learn a lot from interacting with the pawikan. They become aware of protecting and preserving the environment and the vast marine resources of the country.

The children learn a great deal from their exposures with the pawikan. They learn something they normally don’t acquire from schools. The children who interacted with the pawikan also learned how the turtles adopted to land and sea conditions – something they don’t get to learn in school. Just looking at the faces of the children interacting with the pawikan is enough to know that they enjoyed the company of the exotic animals.

But Montemar is not just a place for pawikan. It is in the first place, a place where people can find pristine serenity. It is a place where one can interact with the sea and its surroundings. It is a place where visitors can experience the hospitality of the Bagakeños.

Almost a century ago, the Americans converted half of the Bataan Peninsula into a military reservation. They erected fortifications and installed huge canons supposedly to protect Manila from perceived invading forces. Today, the canons and fortifications had been replaced with recreational watercrafts.

Unfortunately, the American defenses proved to be useless and powerless against the invading Japanese forces. Bagac was the site of many battles where thousands of Japanese soldiers died trying to overrun American defenses in Bagac, Mariveles and Pilar.

Every year, hundreds of relatives of Japanese war veterans still visit the Death March shrine in Bagac. They offer flowers and Buddhist prayers to the thousands of soldiers who died during the war. They sound the giant Buddhist bronze bell at the tower to call for forgiveness and long lasting peace.

The infamous Death March was coined to dramatize the sacrifices and bravery of thousands of ‘battling bastards’ who were forced to walk from Bataan to Pampanga after they surrendered to the Japanese in 1942. The long march started in Bagac and a ‘zero’ kilometer marker was erected by the Filipino American Memorial Endowment to mark the place where man’s brutality to man in this part of the world started.

Because of its historical significance, the town also became a byword to history buffs. The construction of the nuclear power plant in Napot Point, the hosting of the Philippine Refugee Processing Center in Morong, and the Filipino-Japanese Friendship tower in Bagac added more points of interest to the province.

Visitors in Montemar can actually get a glimpse of the mothballed power plant while playing golf at the resort’s nine-hole course. The course has lush green links surrounded by sandtraps and bushes. Talisay trees provide the shade needed by golfers on a hot and humid day. It is also a nice picnic spot.

One thing I like about the place is that it is very near Metropolitan Manila. There may be places similar to Bagac in other parts of Luzon but to me, this place has a unique ambience that continues to give me endless nirvana everytime I indulge in its beauty.

Kids simply find this place the perfect playground. The pool, the hanging bridge, the swings, and the lush bermuda grass provide ample playing fields for the children and their yayas.

So, what else can you ask for in a place called Montemar? The food is exotic and the beer is always cold. A cold shake or a margarita can be mixed in a minute or two by the resident bartender.

And the women are simply breathtaking. A mermaid on the rocks is a perennial offering on a hot summer day in Montemar. Other resorts in Bagac also have their own mermaids on the rocks.

So what else is new in Montemar aside from the pawikan, mermaids, margarita, ice-cold San Miguel, cozy rooms, white sand beach, lobsters and snorkeling?

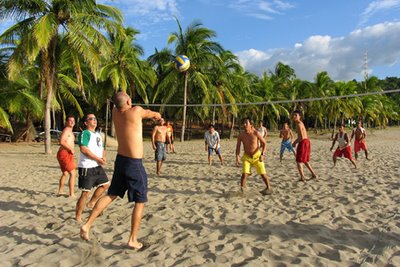

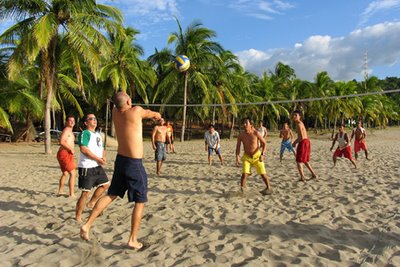

Well, there’s volleyball, adventure hikes to nearby waterfalls and rivers. Mountain climbing or simply hanging out in the bar overlooking the South China Sea.

Lovers can also find Montemar to be enticing enough to have their weddings by the sea. A sizzling bonfire could heat up the fervor among newly-weds just in time to catch the setting sun on the horizon.

Last December, Montemar was the venue of a wedding reception where hundreds of guests from Manila came with their SUVs and luxury sedans. They came to see if it was really true that turtles roam freely in the resort. They came to see how hatchlings race to the sea. They came to embrace the wind and see the famous Montemar sunset.

Yes … the sunset in Montemar is simply breathtaking, especially if you’re listening to Sting’s Dream of the blue turtle. To me, it’s simply nirvana. Now who wants to go to this place? Be my guest.

Author's Note: I spent three months photographing the turtles and the people of Montemar beach. My photo documentation started on November 2005 and ended January 2006. Almost a year after, the turtle population in the resort has tripled, and after being tagged on their fins, have been dispersed to the seas by the management of Montemar under the direct supervision of municipal and provincial environmental officers.

The turtles are beautiful and caring animals of the deep. They should remain free for they are the dwellers of the yonder seas. Man should stop annihilating them. This November, the Montemar people will be releasing more adult Olive ridleys and their hatchlings to the sea in celebration of Pawikan Day.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home